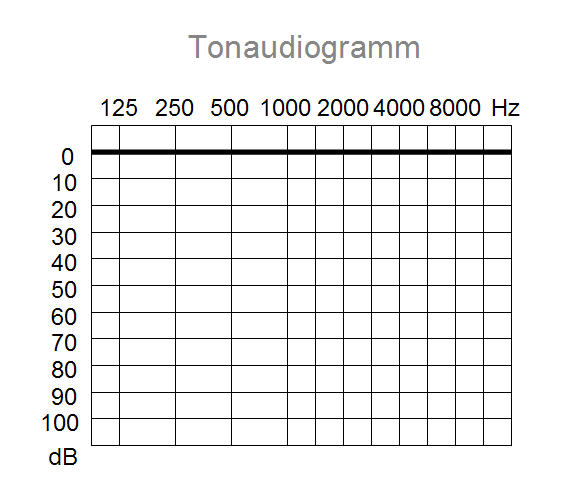

You’ve just finalized your hearing test. The hearing specialist is now entering the room and presents you with a chart, like the one above, except that it has all of these icons, colors, and lines. This is designed to present to you the exact, mathematically precise attributes of your hearing loss, but to you it might as well be written in Greek.

The audiogram adds confusion and complexity at a time when you’re supposed to be concentrating on how to improve your hearing. But don’t let it mislead you — just because the audiogram looks perplexing doesn’t mean that it’s hard to grasp.

After reading through this article, and with a little terminology and a handful of basic principles, you’ll be reading audiograms like a professional, so that you can focus on what really matters: healthier hearing.

Some advice: as you read the article, reference the above blank audiogram. This will make it much easier to understand, and we’ll cover all of those cryptic markings the hearing specialist adds later on.

Understanding Sound Frequencies and Decibels

The audiogram is basically just a diagram that records sound volume on the vertical axis and sound frequency on the horizontal axis. (are you having flashbacks to high school geometry class yet?) Yes, there’s more to it, but at a elementary level it’s just a chart graphing two variables, as follows:

The vertical axis documents sound intensity or volume, measured in decibels (dB). As you move up the axis, the sound volume decreases. So the top line, at 0 decibels, is a very soft, weak sound. As you go down the line, the decibel levels increase, representing increasingly louder sounds until you get to 100 dB.

The horizontal axis records sound frequency, measured in Hertz (Hz). Starting at the top left of the graph, you will see a low frequency of 125 or 250 Hz. As you move over along the horizontal axis to the right, the frequency will progressively increase until it gets to 8,000 Hz. Vowel sounds of speech are normally low frequency sounds, while consonant sounds of speech are high frequency sounds.

So, if you were to start off at the top left corner of the graph and sketch a diagonal line to the bottom right corner, you would be raising the frequency of sound (moving from vowel sounds to consonant sounds) while increasing the volume of sound (moving from fainter to louder volume).

Testing Hearing and Marking Up the Audiogram

So, what’s with all the marks you usually see on this basic chart?

Easy. Start off at the top left corner of the graph, at the lowest frequency (125 Hz). Your hearing specialist will present you with a sound at this frequency by way of headphones, beginning with the smallest volume decibel level. If you can hear it at the lowest level (0 decibels), a mark is created at the convergence of 125 Hz and 0 decibels. If you are not able to hear the 125 Hz sound at 0 decibels, the sound will be presented again at the next loudest decibel level (10 decibels). If you can hear it at 10 decibels, a mark is created. If not, carry on to 15 decibels, and so on.

This same method is reiterated for every frequency as the hearing specialist moves along the horizontal frequency axis. A mark is produced at the lowest perceivable decibel level you can hear for every sound frequency.

In terms of the other symbols? If you observe two lines, one is for the left ear (the blue line) and one is for the right ear (the red line: red is for right). An X is as a rule used to mark the points for the left ear; an O is applied for the right ear. You may observe some other symbols, but these are less vital for your basic understanding.

What Normal Hearing Looks Like

So what is seen as normal hearing, and what would that look like on the audiogram?

Individuals with regular hearing should be able to perceive each sound frequency level (125 to 8000 Hz) at 0-25 decibels. What might this look like on the audiogram?

Take the blank graph, find 25 decibels on the vertical axis, and draw a horizontal line completely across. Any mark made beneath this line may signal hearing loss. If you can perceive all frequencies under this line (25 decibels or higher), then you very likely have normal hearing.

If, however, you can’t perceive the sound of a particular frequency at 0-25 dB, you likely have some type of hearing loss. The smallest decibel level at which you can perceive sound at that frequency establishes the amount of your hearing loss.

By way of example, consider the 1,000 Hertz frequency. If you can perceive this frequency at 0-25 decibels, you have normal hearing for this frequency. If the minimum decibel level at which you can hear this frequency is 40 decibels, for instance, then you have moderate hearing loss at this frequency.

As a summary, here are the decibel levels identified with normal hearing along with the levels connected with mild, moderate, severe, and profound hearing loss:

Normal hearing: 0-25 dB

Mild hearing loss: 20-40 dB

Moderate hearing loss: 40-70 dB

Severe hearing loss: 70-90 dB

Profound hearing loss: 90+ dB

What Hearing Loss Looks Like

So what might an audiogram with signals of hearing loss look like? Given that the majority of instances of hearing loss are in the higher frequencies (labeled as — you guessed it — high-frequency hearing loss), the audiogram would have a downwards sloping line from the top left corner of the graph slanting downward horizontally to the right.

This indicates that at the higher-frequencies, it takes a increasingly louder decibel level for you to perceive the sound. Furthermore, since higher-frequency sounds are linked with the consonant sounds of speech, high-frequency hearing loss impairs your ability to comprehend and follow conversations.

There are a few other, less typical patterns of hearing loss that can turn up on the audiogram, but that’s probably too much detail for this entry.

Testing Your New-Found Knowledge

You now know the basics of how to read an audiogram. So go ahead, book that hearing test and surprise your hearing specialist with your newfound abilities. And just imagine the look on their face when you tell them all about your high frequency hearing loss before they even say a word.